In a

2002 paper, what is

frequently referred to as “Munk’s enigma”, Scripps Institution of

Oceanography’s senior researcher bemoaned the fact researchers could not fully

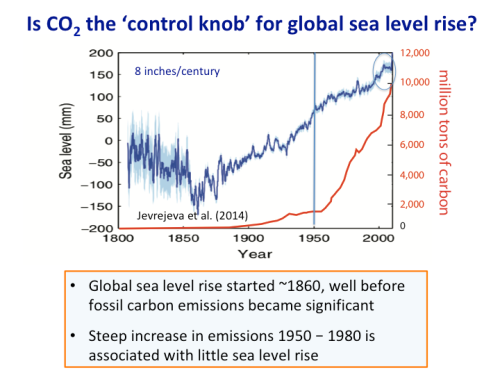

account for the causes of sea level rise. He lamented, “the historic rise

started too early, has too linear a trend, and is too large.” Early IPCC analyses

noted about 25% of estimated sea level rise was unaccounted for. Accordingly, in

2012, an international team of prominent sea level researchers published,

Twentieth-Century

Global-Mean Sea Level Rise: Is the Whole Greater than the Sum of the Parts? (henceforth Gregory 2012). They hoped

to balance struggling sea level budgets by re-analyzing and adjusting estimates

of the contributions from melting glaciers and ice caps, thermal expansion, and

the effects of dam building and groundwater extraction. However, a natural

contribution from any imbalance in groundwater re-charge vs discharge was never

considered. Yet the volume of freshwater stored as groundwater, is second only

to Antarctica’s frozen supply, and 3 to 8 times greater than Greenland’s.

At the risk of oversimplifying, the effects of groundwater

storage can be differentiated between shallow-aquifer effects that modulate

global sea level on year to year and decade to decade timeframes, versus deep

aquifer effects that modulate sea level trends over centuries and millennia.

Researchers are increasingly aware of natural shallow groundwater

dynamics. As noted by

Reager (2016) in

A Decade of Sea Level Rise Slowed by Climate-Driven

Hydrology, researchers had determined the seasonal delay in the return of

precipitation to the oceans causes sea levels to oscillate by 17 ± 4 mm [~0.7

inches] per year. Reager (2016) also argued decadal increases in terrestrial

water storage driven by climate events such as La Nina, had reduced sea level

rise by 0.71 mm/year. Likewise,

Cazenave

2014 had published according to altimetry data, sea level had decelerated

from 3.5 mm/yr in the 1990s to 2.5mm/yr during 2003-2011, and that deceleration

could be explained by increased terrestrial water storage, and the pause in ocean

warming reported by Argo data.

Improved observational data suggest during more frequent La

Nina years a greater proportion of precipitation falls on the land globally and

when routed through more slowly discharging aquifers, sea level rise

decelerates. During periods of more frequent El Niños, more rain falls back onto

the oceans, and sea level rise accelerates. In contrast to La Nina induced shallow-aquifer

effects, deep aquifers have been filled with meltwater from the last Ice Age,

and that water is slowly and steadily seeping back into the oceans today.

Munk’s “Too Linear

Trend” Enigma and Deep Groundwater Discharge

Hydrologists concerned with sustainable groundwater supplies

and drinking water contamination, have been in the forefront of analyzing the volume

and ages of the world’s groundwater, providing greater insight into deep

aquifer effects.

Gleeson (2015) determined, “total groundwater

volume in the upper 2 km of continental crust is approximately 22.6 million

cubic kilometers, twice as much as earlier

estimates. If all 22.6

million cubic kilometers of freshwater stored underground reached the oceans,

sea level would rise 204 feet (62,430 millimeters). Via various isotope

analyses and flow models,

Jasechko (2017)

estimated that between 42-85% of all groundwater stored in the upper 1

kilometer of the earth’s crust is water that had infiltrated the ground more

than 11,000 years ago, during last Ice Age.

Clearly the earth’s groundwater has yet to reach an equilibrium

with modern sea levels. With deep aquifer discharge primarily regulated by

geological pore spaces (in addition to pressure heads), the slow and steady

discharge of these older waters affects sea level rise on century and

millennial timeframes. And, although freshwater discharge from deep aquifers

may be locally insignificant relative to river runoff, deep aquifer discharge

when integrated across the globe could account for the missing contribution to

the sea level rise budgets.

Unfortunately quantifying the groundwater discharge contribution

to sea level rise is extremely difficult, suffering from a low signal to noise

problem. That difficulty is why natural groundwater contributions are often

ignored or brushed aside as insignificant. Although GRACE satellite monitoring

of gravity changes offers great promise for detecting changes in terrestrial

groundwater storage, GRACE cannot accurately separate the relatively small

discharge of deep aquifers from large annual changes in shallow groundwater. In

periods of heavy rains, groundwater increases will mask deep aquifer discharge.

And during a drought, any deep groundwater discharge will likely be attributed

to the lack of rain.

However, estimates of groundwater re-charge via isotope

analyses can provide critical information regards rates of groundwater

re-charge and discharge.

Using the abnormal levels of tritium released during nuclear

testing in the 1950s, plus carbon14 dating,

researchers

have categorized the time since groundwater had last left the surface into 25,

50, 75 and 100-year old age classes. As expected, the youngest water is

concentrated in the shallowest aquifer layers and the proportion of young water

decreases with depth. The estimated volume of 25-year-old or younger

groundwater suggests global groundwater is currently recharging at a rate that

would

reduce sea level by 21 mm/year

(0.8 inches/year).

Water cycle researchers (i.e. Dai and Trenberth) have made the

dubious assumption that the amount of water transported via precipitation to

the land from the ocean is balanced each year by river runoff.

But if the tritium derived estimates are valid,

balancing water cycle and sea level budgets becomes more enigmatic. Clearly a

significant amount of precipitation does not return for decades and centuries.

Intriguingly, comparing the smaller volume of ground water

aged 50 to 100-years-old versus the volume of water 50-years-old and younger

suggests 2 possible scenarios. Either ground water recharge has increased in

recent decades, or if recharge rates averaged over 50 years have remained

steady, then as groundwater ages a significant portion seeps back to the ocean

at rates approaching 1.7 mm/year, a rate that is very similar to 20th

century IPCC estimates of sea level rise.

Groundwater discharge must balance recharge or else it directly

alters global sea levels. When less than 21 mm/year seeps back to the ocean,

then natural groundwater storage lowers sea level. When discharge is greater

than 21 mm/year, then groundwater discharge is raising sea level. Without

accounting for recharge vs discharge, the much smaller estimates of all the other

factors contributing to sea level rise are simply not well constrained.

Higher rates of discharge could account for the enigmatic

missing sea level contributions reported by the IPCC and other researchers (i.e.

Gregory 2012). More problematic, if

discharge proves to significantly exceed recharge, then estimates of contributions

from other sources such as melting ice and thermal expansion may be too high. What

is certain, the current estimates of contributions to sea level from melting

ice and thermal expansion only range from 1.5 to 2.0 mm/year, and those factors

by themselves cannot offset the tritium estimated 21 mm/year of groundwater

recharge. So, what is missing in our current water cycle budgets?

The Importance of Submarine Groundwater Discharge (SGD)

The recharge-discharge imbalance can be reconciled if water

cycle budgets included the difficult-to-measure rates of prolific submarine

groundwater discharge (

SGD). Freshwater

springs bubbling up from coastal sea floors have long been observed. To

reliably replenish drinking water, Roman fisherman mapped their occurrences

throughout the Mediterranean.

Moosdorf (2017)

has reviewed the locations and many human uses of fresh

submarine groundwater discharge around the world.

Recent ecological studies have measured local submarine

groundwater seepages to determine contributions of solutes and nutrients to

coastal ecosystems. But those sparse SGD measurements cannot yet be reliably

integrated into a global estimate.

Rodell

(2015) notes that most water cycle budgets have ignored SGD due to its

uncertainty, so Rodell’s water cycle budget included a rate of SGD equivalent

to 6.5 millimeters/year (~0.25 inch/yr) of sea level rise. However, that estimate

is still insufficient to balance current recharge estimates.

However, with improving techniques, researchers

recently estimated total submarine groundwater

(saline and fresh water combined) discharges suggesting a rate

3 to 4 times greater than the observed

global river runoff, or a volume equivalent to 331 mm/year (13 inches) of sea

level rise. Nonetheless more than 90% of that submarine discharge is saline sea

water, most of which is likely recirculated sea water, and not likely to affect

sea level. Only the fraction of entrained freshwater would raise sea level. To

balance the 21 mm/year ground water recharge, between 6 and 7% of total SGD must

be freshwater and that amount is very likely. Local estimates of the freshwater

fraction of submarine discharge range from 1 to 35%, and on average just less

than 10%. If fresh submarine groundwater discharge approaches just 7% of the

total SGD, it would not only balance current groundwater recharge, but would steadily

raise sea level by an additional 2 mm/year, even if there was no ocean warming and

no melting glaciers.

A Sea Level Rise “Base-flow”

and Paleo-climate Conundrums

Hydrologists seek to quantify the aquifer contributions to

river flow, otherwise known as the “base flow”. During the rainy season or the

season of melting snow, any groundwater contribution is masked by heavy surface

runoff and shallow aquifer effects. However, during extended periods of drought

hydrologists assume the low river flow that persists must be largely attributed

to supplies from deeper aquifers. Streams that dry up during a drought are

usually supported by small shallow aquifers, while reduced but persistent river

and stream flows must be maintained by large aquifers. Using a similar conceptual

approach, we can estimate a possible “base flow” contribution to sea level.

When the continental ice sheets began to melt as the earth

transitioned from its Ice Age maximum to our present warm interglacial, sea

level began to rise from depths ~130 meters lower than today (see graph below).

Melting continental ice sheets drove much higher rates of sea level rise than seen

today, ranging from 10 to 40+ mm/year. Approximately 6,000 years ago, a

consensus suggests the last of the continental ice sheets had melted completely,

the earth’s montane glaciers had disappeared, and Greenland and Antarctic ice

sheets had shrunk to their minimums. The earth then entered a long-term 5000-year

cooling trend dubbed the

Neoglaciation.

Although sea level models forced only by growing glaciers and cooling ocean

temperatures would project falling sea levels, proxy evidence enigmatically suggests

global sea level continued to rise. Albeit at reduced rates, global sea level continued

to rise another 4 meters (Figure 1 below). Although there is some debate

regards any continued contribution from Antarctica and “ocean siphoning”, according

to

Lambeck 2014 about 3 meters of sea level

were added between 6.7–4.2 thousand years ago. That continued sea level rise

could be explained by aquifer discharge, suggesting a minimal “base flow” of ~1.2

mm/year from groundwater discharge.

Similarly, during the Little Ice Age between 1300 and 1850 AD,

montane glaciers as well as Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets, grew and reached

their largest extent in the last 7,000 years. Ocean temperatures cooled by about

1 degree. Yet inexplicably, most researchers estimate global sea level never

dropped significantly. They report sea levels were “stable” during the Little

Ice Age, fluctuating only by tenths of a millimeter. That stability contrasts greatly

with the recent rising trend, that has led some to attribute the current rise

to increasing CO2 concentrations. However Little Ice Age stability defies the physics

of cooling temperatures and increasing water storage in growing glaciers that should

have caused a significant sea level fall. However, that seeming paradox is consistent

with a scenario in which a “base flow” from groundwater discharge would offset any

transfer of waters to growing Little Ice Age glaciers.

Once the growth of Little Ice Age glaciers stopped, and

groundwater base flow was no longer offset, we would expect sea levels to rise

as witnessed during the 19th and 20th centuries. Such a

scenario would also explain Munk’s enigma that sea level rise had started too

early, before temperatures had risen significantly from any CO2-driven warming.

Interestingly, assuming a ballpark figure of a 1.2 mm/year groundwater

base flow, unbalanced groundwater discharge could also explain the much higher

sea levels estimated for the previous warm interglacial, the Eemian.

Researchers estimate sea levels ~115,000 years ago were about 6 to 9 meters

higher than today. That interglacial has also been estimated to have spanned

15,000 years before continental glaciation resumed. Compared to our present interglacial

span of 11,700 years, an extra 3,300 years of groundwater discharge before being

offset by resumed glacier growth, could account for 4 meters of the Eemian’s higher

sea level.

Recent glacier meltwater contribution to sea level is

likely overestimated?

In addition to a groundwater base flow driving the current

steady rise in sea level, meltwater from retreating Little Ice Age glaciers undoubtedly

contributed as well. But by how much?

Researchers have

estimated there was greater glacial retreat (and thus a greater flux of

meltwater) in the early 1900s compared to now. So, current glacier retreat is

unlikely to cause any acceleration of recent sea level rise. Furthermore, we

cannot assume glacier meltwater rapidly enters the oceans. A large proportion

of meltwater likely enters the ground, so it may take several hundred years for

Little Ice Age glacier meltwater to affect sea level.

How fast can groundwater reach the ocean? Groundwater

measured in the Great Plains’ Ogallala Aquifer can flow at a higher-than-average

seepage rate of ~300 mm (~1 foot) in a day, or about the length of a football

field in a year. For such “fast” moving

groundwater to travel 1000 kilometers (620 miles) to the sea, it would require

over 10,000 years! Most ground water travels much slower. The great weight of

the continental glaciers during our last ice age, applied such great pressure

that it forced meltwater to into the ground at much greater rates than

currently observed recharge. And that Ice Age meltwater is still slowly moving

through aquifers like the Ogallala.

(However, its release to the ocean has been sped up by human

pumping.

Recent

estimates suggest that globally, human groundwater extraction currently

exceeds rates of water capture from dam building, so that groundwater depletion

is now accelerating sea level rise.)

How much of the current meltwater can we expect to transit

to the ocean via a slow groundwater route? That’s a tough question to answer.

However, thirteen percent of the earth’s ice-free land surface is covered by

endorheic basins as illustrated by the gray areas shown in the illustration

below.

Endorheic basins have no direct outlets to the ocean. Water entering

endorheic basins only return to the sea via evaporation, or by the extremely slow

route of groundwater discharge. Any precipitation or glacial meltwater flowing

into an endorheic basin could require centuries to thousands of years to flow

back to the oceans.

For example, in 2010-2011, researchers reported that a La

Nina event had caused global sea level to

fall

by the equivalent of 7mm/year (~0.3 inches/year). That dramatic drop happened

despite concurrent extensive ice melt in

Greenland and despite any base flow contribution.

As described by

Fasullo

(2013), GRACE satellite observations detected increased groundwater storage

caused by higher rates of rainwater falling on

endorheic basins, primarily in Australia. Although satellite

observations suggested much of the rainwater remained in the Australian basin,

sea level resumed its unabated rise as groundwater base flow contribution would

predict.

To balance their sea level budgets, researchers assert

melting glaciers have added ~0.8 mm/year to recent sea level rise. The 20th

century retreat of most glaciers is undeniable, but we cannot simply assume all

20th century glacier meltwater immediately reached the oceans. The

greatest concentration of ice, outside of Greenland and Antarctica, resides in

the regions north of India and Pakistan, in the Himalaya and Karakoram glaciers.

Most melt water flowing northward enters the extensive Asian endorheic basins. Likewise,

some of the Sierra Nevada meltwater flows into Nevada’s Great Basin, and some

Andes meltwater flows into the endorheic basins of the Altiplano and Lake

Titicaca as well as the Atacama Desert. It is very likely much of the current glacial

meltwater will then take decades to millennia to reach the ocean and has yet to

impact modern sea levels. If the glacial melt water contribution to sea level

is overestimated, then, the unaccounted-for contribution to sea level rise

becomes much larger than initially thought.

Accurate Attribution of Groundwater Discharge and Recharge Will Constrain

Sea Level Contributions

Using a combination of GRACE gravity data that measured changes

in ocean mass, altimetry data that measured changes in ocean volume and Argo

data that measured heat content,

Cazenave

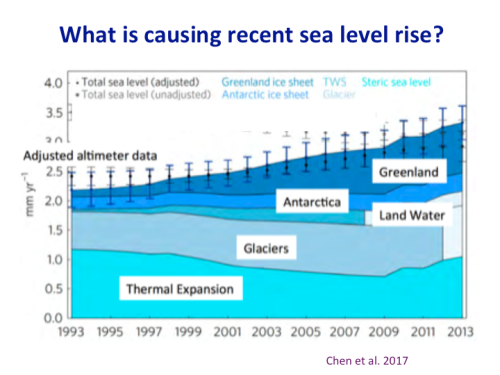

(2008) used 2 different methods and both estimated the contribution from

increased ocean heat to be about 0.3 to 0.37 mm/year.

Jevrejeva

(2008) calculated a similar heat contribution. Other researchers suggest

thermal expansion contributes 1.2 to 1.5 mm/year (i.e.

Chambers 2016).

Such large discrepancies reveal contributing factors to sea level rise are not yet

reliably constrained.

One of the great uncertainties in sea level research are

glacial isostatic adjustments.

Researchers have subjectively adopted various

Glacio-isotatic adjustment models with recommended adjustments ranging from 1

to 2 mm/year. For example, although GRACE gravity estimates had not detected

any added water mass to the oceans, Cazenave (2008) added a 2 mm/year

adjustment, as illustrated from her Figure 1 below. Other

researchers

only added a 1 mm/yr adjustment.

1)

Assume the

contribution from glacier melting was greater than previously estimated.

But

greater

melting rates were documented for the 30s and 40s, and the likelihood that

some glacier meltwater is still trapped as groundwater, suggests the glacier

meltwater contribution has been overestimated.

2)

Assume an

increased contribution from thermal expansion.

3)

Assume Greenland

positively contributed to sea level throughout the entire 20th

century.

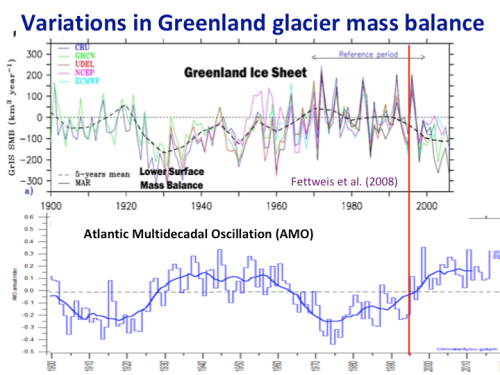

Greenland has undoubtedly

contributed to episodes of accelerating and decelerating sea level changes, but

the greatest rate of Greenland warming occurred during the

1920s

and 30s.

Previous

researchers suggested Greenland glaciers have oscillated during the 20

th

century but had been stable from the 60s to 1990s.

Although there was increased surface melt in

the 21

st century, culminating in 2012, that melt rate has since declined.

And according to the

Danish

Meteorological Institute, Greenland gained about 50 billion tons of ice in

2017 which should have lowered sea level in 2017.

Clearly Greenland cannot explain the

enigmatic steady 20th century sea level rise.

4)

Assume

reservoir water storage balanced groundwater extraction.

But

net

contributions from groundwater extraction vs water impoundments and other

landscape changes are still being debated. For

the period 2002–2014 landscape changes have

been estimated to have reduced sea level by −0.40 mm/year versus IPCC

estimates of contributing 0.38 mm/year from 1993–2010 to sea level rise.

5)

Assume

the remaining unaccounted contribution to sea level rise is small enough to be

attributed to melting in Antarctica.

Debatably, Antarctic melting is too

often used as the catch-all fudge factor to explain the unexplainable. Furthermore,

there is

no

consensus within the Antarctic research community if there have been any human

effects on Antarctica’s ice balance. Regions that are losing ice are balanced

by regions that are gaining ice. Claims of net ice loss have been countered by

claims of net ice gain such as

NASA

2015. Additionally, unadjusted GRACE gravity data has suggested no lost ice

mass and all estimates of ice gains or loss depend on which Glacial Isostatic

Adjustments modelers choose to use. We cannot dismiss the possibility that

unaccounted for groundwater discharge has been mistakenly attributed to hypothetical

Antarctic melting?

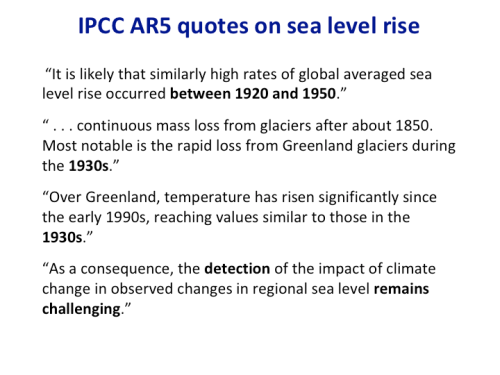

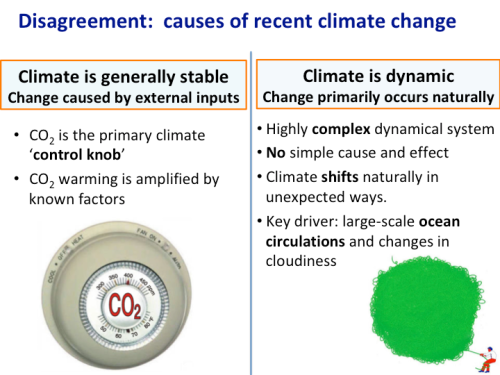

A better accounting of natural groundwater discharge is

needed to constrain the range of contributions to sea level rise suggested by researchers

such as Gregory 2012. The greater the contribution from groundwater discharge,

the smaller the adjustments used to amplify contributions from meltwater and

thermal expansion. Until a more complete accounting is determined, we can only

appreciate Munk’s earnest concern. How can we predict future sea level rise if

we don’t fully understand the present or the past?